Table of content:

- Magna Graecia

- Tarentum – 282 BC

- Tarentum – 281 BC

- Roman expansionism

- Pyrrhus of Epirus

- The Audacious Pyrrhic War – 280 BC

- 280BCE-A Battle of Heraclea

- The Audacious Pyrrhic War – 279 BC

- 279BCE-A Battle of Asculum

- The Audacious Pyrrhic War – 278 BC

- 278BCE-A Battle of Venusia

- 278BCE-B Battle of Rhegium

- 278BCE-C Siege of Syracuse

- 278BCE-D Battle of Eryx

- 278BCE-E Siege of Lilybaeum

- The Audacious Pyrrhic War – 277 BC

- 277BCE-A Battle of the Cranita hills

- The Audacious Pyrrhic War – 276 BC

- 276BCE-A Battle of the Strait of Messina

- The Audacious Pyrrhic War – 275 BC

- 275BCE-A The Badass Battle of Beneventum

- The Mamertines

- Cassius Dio

- Plutarch

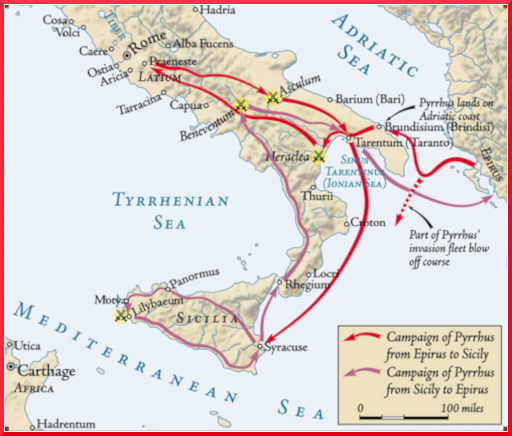

The Pyrrhic War (280–275 BC) was a war largely fought between the Roman Republic and Pyrrhus, King of Epirus, whom had been asked by the people of the Greek city of Tarentum in Southern Italy to assist them in their war against the Romans.

A skilled audacious commander, who brought with him a contingent of war elephants, Pyrrhus enjoyed initial success against the tough Roman legions, but would incur heavy losses even when victorious.

Plutarch wrote of Pyrrhus that he purportedly remarked, at the outcome of his second successful battle against the Romans — yet again won at the expense of heavy casualties, including many of his leading officers —

“One more such victory (against the Romans) and we shall be utterly ruined.“

Whereas Rome could afford to replenish its heavy losses endured in the first two battles of the Pyrrhic War, due to the presence of a large contingent of male citizens of fighting age, eager and willing to strengthen its harsh fighting spirit,

Phyrrus found himself confronted with the unmistaken reality that he was a stranger in a strange land unable to make up for his losses in a manner that would allow him to defeat Rome.

Despite trampling Rome’s legions in two consecutive battles, the first of which he nearly succeeded in wiping out his opponent with a dashing Elephant maneuver against the Roman flank, a testimony to his considerable skills as a leader and military commander, these initial victories would amount to little in the long run, as he was fighting a much larger enemy determined to succeed at any and all cost.

With a sizable chunk of his infantry and cavalry on “loan” from Ptolemy II of Egypt, accompanied by a pledge to return these troops after two years of service, his finances subject to the whimsical nature of Hellenistic Kings and the initial support he’d received from his Italian allies stifled by false promises, exaggeration and raw fear in the face of Rome’s unforgiving tenacity,

Pyrrhus decision to quarrel with both Rome and Carthage may be viewed somewhat along the lines of Usain Bolt’s attempt to become a professional soccer player… one could predict upfront that it was never going to be done in a manner that would make things right.

Although incredibly gifted in one major aspect of the Ancient Arena — warfare — he lacked the ability to capitalize upon his whirlwind victories to a degree that his mastery of destruction would grant him increased stature within the ranks of those unaccustomed to the appalling sight of blood and guts.

This inability to gain a strategical foothold on relevant affairs, despite what may be viewed as a very successful start of his slug match with the Roman State (and later on against Carthage), has become known to History as a “Pyrrhic victory” (the inability to capitalize on initial gains when viewed in the long run).

Worn down by his costly battles against the Roman State and its steadfast refusal to negotiate in even the smallest of military matters, such as his proposed handover of Roman prisoners of war, Pyrrhus moved his army to the island of Sicily in order to quarrel with the Carthaginians instead.

This “vagueness” of commitment and purpose beyond the battlefield, which would often characterize his actions when not involved in reducing complex human affairs to several hours of blood and guts would prove disastrous in terms of his ambition to build or project any long-term moral incentive.

Whether by nature or nurture, this lack of clear-sighted political aims and objectives would cause him to shift his focus from Rome, to Sicily, to Africa until even the quarrelsome Sicilian Greeks got fed up with his despotic behavior and his inability to handle their worldly affairs and war against Carthage in a proficient manner.

Despite several years of successful campaigning in Sicily (278–275 BC), besieging and capturing several major cities but ultimately failing to score a decisive victory against the Carthaginian forces still present on the Island, his decision to return to Italy in the year 275 BC, appears to be driven by a strong emotional need to prove to himself, and those aware of his inconsistencies when not consumed by the stringent pressure to do-or-die, that he is the ace commander capable of finishing off the Roman menace once and for all.

The last battle of the Pyrrhic War, at Beneventum, was a close call;

a hard fought encounter between a highly skilled Greek commander hungry for Glory, and an even more determined frugal incorruptible Roman Consul eager and willing to serve the common good of the Republic, displaying some of the same characteristics that would ultimately allow Bernard Montgomery to defeat the exceptional German battle commander Erwin Rommel during his Africa Campaign in World War II.

The Battle of Beneventum could be either viewed as indecisive, based on the high number of casualties on both sides, or a victory for the Romans, in that it would force Pyrrhus to retreat with his army from the Italian Peninsula.

Three years later, in 272 BC, the ever tenacious Romans, would finally succeed in capturing the city of Tarentum.

The Pyrrhic War was notable — from a military perspective — in that it signified the first major encounter of the City of Rome with the professional armies of the Hellenistic states of the Eastern Mediterranean, against whom it would fight many more battles in the foreseeable future.

Rome’s victory over Pyrrhus, The Vague Alexander, would soon draw the attention of these states to the emerging power of Rome, encouraging Ptolemy II, the King of Egypt, to establish diplomatic relations with the Roman state.

After the Pyrrhic war, Rome asserted its hegemony over Southern Italy, only to encounter an even more legendary opponent, so skillful in defeating the tough Roman Legions that his persistent Rage Against the Machinery of Rome, known as the Hannibalic War, would come to threaten the very survival of the Roman State as such.

I. Magna Graecia

A.N.C.I.E.N.T G.R.E.E.K C.O.L.O.N.I.Z.A.T.I.O.N

VID-001: Megas Hellas – The Greeks of Italy and Sicily

II. Tarentum – 282 BC

VID-001: The Ancient History of Tarentum

Pre-war wranglings in Tarentum in 282 BC:

- Ten Roman ships appear off the coast of Tarentum.

- Philocharis of Tarentum views Cornelius’ expedition as a violation of an ancient naval treaty, attacks the expedition, sinking four ships and capturing one.

- Tarentum attacks the Roman garrison at Thurii, expels it and sacks the city.

- Rome dispatches an embassy to Tarentum, which is rejected and insulted by The Tarentines.

- The Roman senate declares war on Tarentum.

- Consul Lucius Aemilius Barbula ceases hostilities with the Samnites, and moves against Tarentum.

III. Tarentum – 281 BC

VID-001: Ptolemy I and Ptolemy II

VID-002: Ptomely family tree

Pre-war wranglings in Tarentum in 281 BC:

- The Tarentines sent envoys to call on Pyrrhus to protect them against the Romans; Pyrrhus is encouraged by the claim that the Samnites, Lucani and Messapi had gathered an army of 50,000 infantry and 20,000 cavalry.

- Pyrrhus asks Antiochus I for money and Antigonus II to lend him ships to carry his army to Italy.

- Ptolemy II lends him 5,000 infantry and 2,000 cavalry on the condition that they would be returned to him after a two year period of service.

- Pyrrhus appoints Ptolemy II as guardian of his kingdom, to govern in his absence, while fighting the Pyrrhic War.

IV. Roman expansionism

R.O.M.A.N E.X.P.A.N.S.I.O.N.I.S.M

VID-001: Roman Expansionism

VID-002: Roman Expansionism & The 3rd Punic War

V. Pyrrhus of Epirus

VID-001: Pyrrhus of Epirus, the Fool of Hope

POD-001: TTC Lecture 23 – Pyrrhus

POD-002: Good Guy Pyrrhus

POD-003: Pyrrhus of Epiros

VI. The Audacious Pyrrhic War – 280 BC

T.H.E A.U.D.A.C.I.O.U.S P.Y.R.R.H.I.C W.A.R

VID-001: Pyrrhus and the Pyrrhic War

VID-002: Campaigns of Pyrrhus

VID-003: Battles Of Heraclea 280BC and Asculum 279BC

VID-004: The Costliest War of the Ancient World

VID-005: What Happened After The Pyrrhic Wars?

POD-001: Ancient Rome History – Part 1 Pyrrhic War

POD-002: Ancient Rome History – Part 2 Pyrrhic War

The Pyrric War events of 280 enumerated:

- Pyrrhus sends Cineas ahead to Tarentum

- Pyrrhus also sends Milo ahead to Tarentum

- Pyrrhus sets sail for Italy.

- Pyrrhus arrives in Terentum, bringing war elephants.

- The Samnites, Lucani, Bruttii and Messapi ally with Pyrrhus.

- Pyrrhus offers to negotiate with the Romans.

- Pyrrhus defeats the Romans at the Battle of Heraclea.

- Locris sides with Pyrrhus.

- Rhegium asks for Rome’s protection. The Roman place garrison in the city. These soldiers seize it, killing many of its people.

- The consul Tiberius Coruncanius is recalled from Etruria to defend Rome.

- The ranks of the legions of the consul Publius Valerius Laevinus are replenished.

- Pyrrhus advances on Capua, Publius Valerius Laevinus garrisons the city.

- Pyrrhus sets out for Neapolis, but he does not accomplish anything

- Pyrrhus advances as far as Anagni or Fregellae in Latium and then goes to Etruria.

- Pyrrhus finds out the Etruscans allied with Rome; the two Roman consuls pursue him.

- Pyrrhus withdraws and gets close to Campania. Laevinus confronts him with an army. Pyrrhus refuses battle and returns to Tarentum.

- Mago, a Carthaginian commander goes to Rome with a fleet of 140 warships to offer help. The Roman senate declines the offer.

- Mago goes to see Pyrrhus privately, ostensibly to negotiate peace. In reality he wanted to check his intentions regarding a plea for help by the Greek cities in Sicily.

- Gaius Fabricius Luscinus is sent on a mission to Pyrrhus to negotiate the release of Roman prisoners of war. Pyrrhus attempts to bribe Fabricius, and when he cannot, releases the prisoners without ransom.

- Pyrrhus sends Cineas to Rome as the ambassador of Pyrrhus to negotiate a peace or a truce.

- Appius Claudius Caecus calls for Pyrrhus to leave Italy and for Cineas to leave Rome immediately. The senate seconds him.

- Cineas returns to Pyrrhus, and calls the Roman senate “a parliament of kings”. He also assessed that the Romans have twice as many soldiers as those who fought at the previous battle and many more reserve men.

VI-280BCE-A. Battle of Heraclea

VID-001: Battle of Heraclea 280 BC

VID-002: Battle of Heraclea – Part I

VID-003: Battle of Heraclea – Part II

VID-004: The Eagle King Has Landed

Pyrrhus did not march against the Romans while he was waiting for his allies’ reinforcements.

When he finally understood that his allies had deceived him with regards to their available troop numbers and their apparent lack of willingness to commit these minor forces to battle, he decided to confront the Romans on his own on a plain near the river Siris (modern Sinni), between Pandosia and Heraclea.

Pyrrhus took up position there and awaited the arrival of Rome.

Before the fight he sent diplomats to the Roman consul, proposing that he’d be willing to arbitrate the conflict between Rome and the population of Southern Italy, without the need for further bloodshed, asserting his allies recognized him as their representative judge and demanding the Romans extend towards him the same level of courtesy in dealing with these sordid affairs.

The Romans denied his request, and entered the plain on the right of the Siris river, where they set up camp.

It is unknown as to how many troops Pyrrhus had left behind in Tarentum but it is estimated he was accompanied by 25–35,000 troops at Heraclea.

He took up position on the left bank of the Siris river, hoping that the Romans would experience difficulties in crossing the river, allowing him to exploit a tactical terrain advantage in countering their attack.

He set up some light infantry units as scouts close to the riverbed, ordering them to immediately inform him should the Romans begin to cross, as he planned to attack them with his cavalry during their crossing.

The Roman commander Valerius Laevinus had about 42,000 soldiers under his command, including cavalry, velites, and spearmen.

The battle of Heraclea would be the first time in history that two very different juggernauts of war clashed: the Roman Legion versus the Macedonian Phalanx.

At dawn, the Romans started to cross the river Siris.

Ahead of the infantry crossing the Roman cavalry attacked the nearby scouts and light infantry, who were forced to flee.

When Pyrrhus learned that the Romans had begun traversing the river he led his Macedonian and Thessalian cavalry to counterattack the Roman crossing.

His infantry, with peltasts, archers and heavy infantry, quickly descended onto the riverbed.

The Epirote cavalry successfully disrupted the Roman battle formation and then withdrew.

Pyrrhus’ peltasts, slingers, and archers began to sling and fire as his sarissa-wielding phalanxes moved forward to attack.

The infantry line of Pyrrhus was near equal to the Romans’ in length , although Pyrrhus had a small advantage in numbers, the phalanx being deeper by design than the acies triplex of the legion.

His phalanxes initiated no less than seven separate attacks, but in each instance failed to dislodge or pierce the tough legionnaire stance.

In squaring off with these legionnaires the Macedonian phalanx had met a foe that was equally tough in their willingness to fight but unlike their monolithic strength possessed a more localized flexible type of aggression that would emerge from Roman unit commanders, encouraged to act with initiative and decisiveness where occasion and good fortune would permit.

The Romans, never willing to concede, initiated several attacks of their own, yet despite their superior infantry tactics, failed to break the cohesion of the phalanx, and for a while the outcome of the battle hung in the air.

At some point, the battle became so evenly matched that Pyrrhus — realizing that if he were to fall in combat, his soldiers would lose heart and run — made the split second decision to switch his armor with one of his bodyguards, lest he fall in battle.

This bodyguard was subsequently killed, and word began to spread through the ranks that Pyrrhus had fallen… a disaster for any army in Antiquity where much of the courage of the men engaged in loud, bloody, rough close-combat rested on their belief in the strength, courage and trustworthiness of their leader.

Pyrrhus ranks began to waver, and the Romans let loose a thunderous cheer at this unexpected turn of events.

Grasping the magnitude of the situation, Pyrrhus rode forward, bare-headed, galloping along his lines to prove to his men not only that he was still alive but that he was determined to lead them to victory.

This show of bravery strengthened his armies resolve and a massive roar swept through the Greek infantry lines as the battle raged on.

Unable to make any significant gains against the Roman Legionnaires through the use of infantry tactics, Pyrrhus decided to deploy his war elephants, held in reserve until now.

With the Roman cavalry threatening his flanks, Pyrrhus let loose onto the Roman dominion these huge beasts of war. (henceforth known to the Roman imagination as “Lucian oxes”, a reference to the place where they were first encountered.)

Aghast at the sight and smell of these enormous unfamiliar beasts the Roman cavalry horses instantly panicked and galloped away, causing chaos and confusion to overtake the Roman ranks, forcing an unprecedented rout upon the Roman legions.

Pyrrhus, sensing victory was his for the taking, unleashed his elite Thessalian cavalry upon the faltering legions, witnessing scenes of brutal carnage with panicked soldiers wildly retreating across the river as fast as their legs would carry them.

In the opinion of Dionysius, the Romans lost 15,000 soldiers and had thousands taken prisoner; Hieronymus states 7,000. Dionysius totaled Pyrrhus’ losses at around 11,000 soldiers, 3,000 according to Hieronymus.

Either way, the battle of Heraclea represented the earliest of Pyrrhus’ costly victories against Rome, and one of the rare instances upon which the Roman War Machine lost its tactical and strategic cohesion to a degree as to allow itself to be smashed to pieces.

(source: Wikipedia)

VII. The Audacious Pyrrhic War – 279 BC

The Pyrric War events of 279 enumerated:

- Pyrrhus invades Apulia, and is confronted by the Roman army.

- Pyrrhus defeats the Romans at the Battle of Asculum, but suffers heavy losses.

- The Carthaginians and the Romans conclude an alliance treaty.

- When Gaius Fabricius discovers a plot by Pyrrhus’ doctor, Nicias, to poison him; he sends warning to Pyrrhus.

- The Greek cities in Sicily ask Pyrrhus for help against the Carthaginians. Pyrrhus agrees.

- Cineas goes to Rome again, but he is unable to negotiate peace terms.

- A rebellious Roman garrison at Rhegium seizes the town, killing many of its people. The Romans retake the city and execute the rebels.

- Joint Roman-Carthaginian expedition sent to Rhegium.

VII-279BCE-A. Battle of Asculum

VID-001: Pyrrhus vs. Romans and Carthaginians

VID-002: Battle Of Asculum (279 BC)

Cassius Dio wrote that during the winter of 280/279 BC both sides prepared for the next battle.

In the spring of 279 BC, Pyrrhus invaded Apulia. Many places were captured or capitulated. The Romans came upon him near Asculum and encamped opposite him.In Plutarch’s account, after resting his army, Pyrrhus marched to Asculum to confront the Romans.

According to Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Pyrrhus had 70,000 infantry, of whom 16,000 were Greeks.

The Romans had more than 70,000 infantry, of whom about 20,000 were Romans (four legions which at the time had 4,000 men), the rest being troops from allies.

The Romans had about 8,000 cavalry and Pyrrhus had slightly more, plus nineteen elephants.

The 1st century AD Roman senator Frontinus estimated a strength of 40,000 men for both sides.

Pyrrhus had men from Thesprotia, Ambracia, and Chaon, two cities and a district in Epirus, and mercenaries from the Aetolians, Acarnanians, and Athamanians. These Greeks fought in the Macedonian Phalanx battle formation. He had cavalry squadrons from Thessaly. The Greeks of the city of Tarentum, in southern Italy, were allies of Pyrrhus. Pyrrhus also had allies from three Italic peoples in southern Italy: the Bruttii, Lucani, and Samnites.

Among the allies of Rome mentioned by Dionysius of Halicarnassus there were the Frentani, Marrucini, Paeligni, Dauni, and Umbrians. There might also have been contingents from the Marsi and Vestini, who were also allies of Rome.

Since Pyrrhus’ elephants had caused much terror and destruction in the Battle of Heraclea, the Romans devised special wagons against them. They were four-wheeled and had poles mounted transversely on upright beams. They could be swung in any direction. Some had iron tridents, spikes, or scythes, and some had ‘cranes that hurled down heavy grappling irons’. Many poles protruded in front of the wagons and had fire-bearing grapnels wrapped in cloth daubed with pitch. The wagons carried bowmen, hurlers of stones, and slingers who threw iron caltrops and men who threw grapnels on fire against the trunks and faces of the elephants.

Pyrrhus lined up the Macedonian phalanx of the Epirots and Ambracians, mercenaries from Tarentum with white shields, and the Bruttii and Lucani allies on the right wing.

The Thesprotians and Chaonians were deployed in the centre next to the Aetolian, Acarnanian, and Athamanian mercenaries.

The Samnites formed the left wing.

On the right wing of the cavalry were the Samnite, Thessalian, and Bruttii squadrons and Tarentine mercenaries.

On the left wing were the Ambracian, Lucanian, and Tarentine squadrons and Acarnanian, Aetolian, Macedonian, and Athamanian mercenaries.

He divided the light infantry and the elephants into two groups and placed them behind the wings, on a slightly elevated position.

Pyrrhus had an agema of 2,000 handpicked cavalrymen behind the battle line to help hard-pressed troops.

The Romans had their first and third legions on the right wing. The first faced the Epirot and Ambracian phalanx and the Tarentine mercenaries. The third faced the Tarentine phalanx with white shields and the Bruttii and Lucani. The fourth legion formed the center. The second legion was on the right wing. The Latins, Volsci, and Campanians (who were part of the Roman Republic) and Rome’s allies were divided into four legions which were mingled with the Roman legions to strengthen all the lines. The light infantry and wagons which were to be deployed against the elephants were outside the line. Both the Roman and the allied cavalry were on the wings.

(source: Wikipedia)

[Note by Mako the Poet:

Given that there exist several differing historical accounts of the Battle of Asculum, it would be safe to assume that the Romans, while being adept at copying successful war strategies and often learning from their opponents failures, would/could not yet have mastered the art of dealing with War Elephants after just one disastrous encounter. We may therefore presume they were once again primarily defeated due to Pyrrhus skillful deployment of these same War Elephants, either on the first day of battle or the second, depending on which historical account you prefer to believe. It must have been quite a sight though to witness this procession of “anti-elephant” wagons and devices the Romans came up with in an attempt to deal with these terrifying War Elephant tactics.]

VIII. The Audacious Pyrrhic War – 278 BC

The Pyrrhic War events of 278-275 enumerated:

- During his second consulship, after Pyrrhus went to Sicily, Gaius Fabricius Luscinus, is sent against the rebel garrison at Rhegium. He seizes the city and restores it to its people. The surviving rebels are taken to Rome and executed for treason.

- The Carthaginians and the Romans conduct an operation against the rebel Roman garrison which had seized Rhegium

- Pyrrhus leaves Italy and crosses over to Sicily.

- The Carthaginians blockade Syracuse

- Pyrrhus lands at Catana and marches on Syracuse, the Carthaginians leave.

- Sosistratus and Thoenon hand over Syracuse to Pyrrhus. Pyrrhus arranges peace between them.

- Embassies from many Sicilian cities come to Pyrrhus offering their support.

- Pyrrhus takes control of Agrigentum and thirty other cities which previously belonged to Sosistratus.

- Pyrrhus attacks the territory of the Carthaginians in Sicily.

- Pyrrhus captures Heraclea Minoa, Azones, Eryx and Panormus. The other Carthaginian or Carthaginian-controlled cities surrender

- Pyrrhus defeats the Mamertines.

- Pyrrhus starts the siege of Lilybaeum

- The Carthaginians start negotiations. Pyrrhus tells them to leave Sicily.

- Pyrrhus abandons the siege of Lilybaeum.

- Pyrrhus decides to build a fleet to invade Africa to conquer Carthage.

- To man his fleet Pyrrhus treats the Greek cities in Sicily in a despotic and extortionate manner.

- Pyrrhus has Thoenon of Syracuse executed on suspicion of treason, and his despotic behaviour makes him unpopular with the Sicilians.

- The Greek cities in Sicily turned against Pyrrhus. Some of them sided with Carthage, others called in the Mamertine mercenaries.

(source: Wikipedia)

VIII-278BCE-A. Battle of Venusia

VIII-278BCE-B. Battle of Rhegium

VIII-278BCE-C. Siege of Syracuse

VIII-278BCE-D. Battle of Eryx

VIII-278BCE-E. Siege of Lilybaeum

IX. The Audacious Pyrrhic War – 277 BC

IX-277BCE-A. Battle of the Cranita hills

B.A.T.T.L.E O.F T.H.E C.R.A.N.I.T.A H.I.L.L.S

VID-001: Roman-Samnite Wars

VID-002: The Samnite Wars

VID-003: Roman expansion in Italy

VID-004: The Latin and Samnite Wars

VID-005: Samnites and Pyrrhus

PRIM-001: Appian – Samnite Wars I

PRIM-002: Appian – Samnite Wars II

X. The Audacious Pyrrhic War – 276 BC

X-276BCE-A. Battle of the Strait of Messina

B.A.T.T.L.E O.F T.H.E S.T.R.A.I.T O.F M.E.S.S.I.N.A

POD-001: Battle of Messina Strait 276 BCE

XI. The Audacious Pyrrhic War – 275 BC

XI-275BCE-A. The Badass Battle of Beneventum

B.A.D.A.S.S B.A.T.T.L.E O.F B.E.N.E.V.E.N.T.U.M

VID-001: Pyrrhus vs. Everyone

VID-002: Battle Of Beneventum

PRIM-001: Plutarch, Parallel Lives, The Life of Pyrrhus

PRIM-002: Plutarch, Parallel Lives, The Life of Pyrrhus

PRIM-003: Livy on Pyrrhus

PRIM-004: Plutarch on Pyrrhus’ Sicilian campaign

POD-001: The Hellenistic Age Podcast

POD-002: The Hellenistic Age Podcast

POD-003: The Campaigns of Pyrrhus of Epirus

XII. The Mamertines

XIII. Cassius Dio

XIV. Plutarch

“I write this… out of pity to the weakness of human nature.”